Demystifying Generative Autonomy

Demystifying Generative Autonomy

This is Part IV in a series on building a framework for appreciating generative art. In Part I, “Demystifying Generative Art,” Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) builds the case for such a framework. In Part II, “Demystifying Generative Aesthetics,” Bauman examines generative outputs—the results of generative systems. In Part III, "Demystifying Generative Systems," he examines generative systems themselves.

Now in Part IV, Bauman investigates another framework component, autonomy—control within generative systems. The essay includes Bauman’s discussions with Christiane Paul, Matt DesLauriers, Sougwen Chung and Zach Lieberman.

“If I had to describe what I’m doing in a single sentence, it would be ‘the drive towards program autonomy.’”

-Harold Cohen

What does generative art—art using autonomous systems—fundamentally prioritize? You’re speaking to a curious friend who’s unfamiliar with it.

How can you help them understand what’s special about generative art while also conveying that it’s just like any other form of art? What’s it really about?

It’s art rooted in the sharing of control—co-creation between artist and system, whether it’s algorithm, AI or material.

The examination of this relationship and its control dynamic is “autonomy,” how much agency each author—human artist, system or audience—has over the creative process.

Authorship, agency and creativity structure this article and serve as the backbone to understanding autonomy. Together they sketch the relationship between artist, system and viewer that not only produces art but also reveals an artist’s cognitive self-portraiture—their thoughts, process and even worldview. Systems reflect this worldview, integrating decisions, constraints and creative intentions while autonomously contributing to introduce novelty beyond individual authorship.

To understand a generative work more fully, you must look beyond the systems and their outputs in isolation to the relationship between artist, system, viewer and output—the realm of autonomy. To understand autonomy, we first must understand authorship, agency and creativity.

- Authorship: Who are the entities creatively responsible for a particular work—between human artist, system, program, computer, AI model, GAN, audience?

- Questions raised: Can machines, computers or AI be authors/artists? What’s the threshold for authorial credit? How can I think about the authorship of this work, artist or practice?

- Questions raised: Can machines, computers or AI be authors/artists? What’s the threshold for authorial credit? How can I think about the authorship of this work, artist or practice?

- Agency: How much control does each author have?

- Questions raised: How much control is the artist giving up? Why is the artist choosing to cede control? To whom or what is the artist sharing control with? How does that choice empower the artist?

- Questions raised: How much control is the artist giving up? Why is the artist choosing to cede control? To whom or what is the artist sharing control with? How does that choice empower the artist?

- Creativity: How do the authors exercise their agency to express “new, surprising and valuable ideas?”1

- Questions raised: How do autonomy, authorship and agency choices impact creative choices? How much hand does the artist reveal and why? How were the system’s constraints devised and what do they reveal about the artist’s thinking? How did the authorship and agency choices assist in producing something “new, surprising and valuable?”

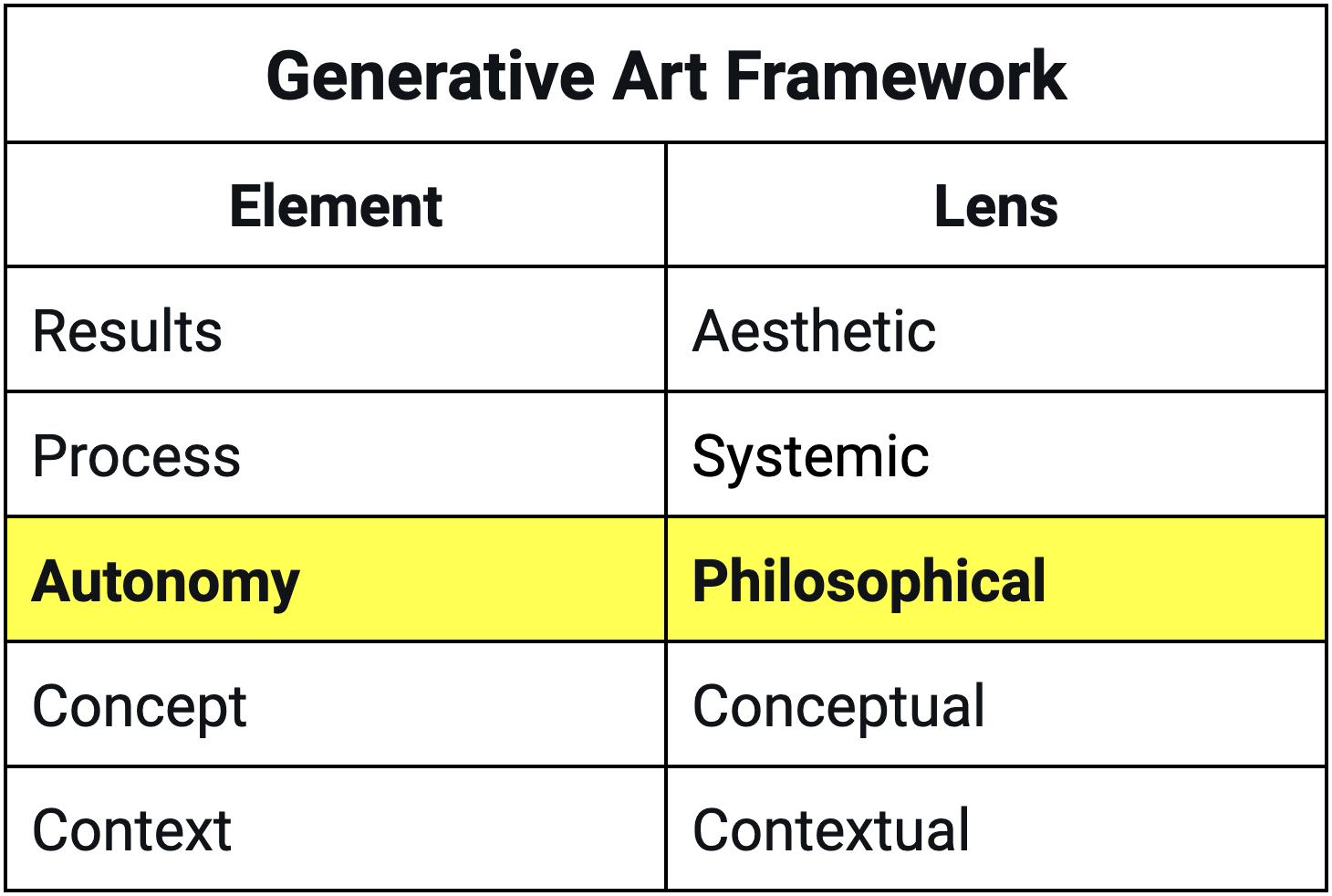

Understanding and appreciating autonomy opens avenues to addressing work on a philosophical or theoretical level—another layer or lens through which to more deeply engage with generative art. Other lenses include aesthetic, systems-based, conceptual or contextual. Lenses supply different perspectives on approaching generative art—the various layers of the art form.

.jpg)

Authorship: Whose Autonomy?

If generative art involves the inherent autonomy of a system, what are those implications for authorship—who is the artist?

First, can a system be an author? With human authorship—like duos Entangled Others, Operator or Beach House—we don’t ask, “Yes, but which of you is really the artist?” We intuitively accept they are both “the artist.” It would be absurd to think that one shouldn’t be considered “the artist” at all.

Can a human artist and non-human system have this same relationship? They can but not all necessarily do. When Harold Cohen spoke about AARON as “his other self,” it indicated that their relationship reached that of human artistic duos; they were inseparable. Few artists may describe the artist-system relationship as so collaborative that the system also becomes “the artist.” But analyzing the gray areas in the relationship can pinpoint fundamental elements of an entire career.

For example, authorial questions remain to this day about whether AARON should continue making work now that Cohen has passed. It can be difficult to discern what Cohen himself would have wanted. Cohen seemed to be conflicted, “joking” about “being the first artist in history to have a posthumous exhibition of new work,” yet referring to AARON as “his other self.” Can Cohen and AARON be separated? Any future versions of AARON—out of necessity involving another artist—would be different. Artist and Cohen’s son, Paul Cohen, agrees. Despite what some say are his father’s wishes, Paul sees the duo of Harold Cohen and AARON as inseparable.

Authorial questions apply to any autonomous system, including computers, algorithms, code, generative and non-generative AI and physical techniques. Besides sorting out who made what, authorship inquiries reveal the intimacy level—connection—between artist and system. We group authorship into three categories—arranged according to levels of autonomy—based on to whom the artist shares control: procedure, community or collaborator.

Procedure

Artists ceding control to procedural systems include short and long-form generative art, GANs and most material (physical) work. The co-creative element consists of following the artist’s rules while adding randomness. Examples include humans drawing lines on a wall in a Sol LeWitt work or an algorithm that uses a transaction hash to determine the variables of a generative artwork. This level of autonomy can be fairly low and many artists may not ascribe authorship to such systems. But is it so black and white?

If you participate in art where you give up control, you’re ceding some level of authorship, which means you’re involving a co-creator. This system work—including the 1960s Systems art of Lawrence Alloway and the Max Bense tree of cybernetic and computer art—begs the question as to how much autonomy—freedom or decisionmaking—until authorship begins.

Why would artists choose to give away their own autonomy and authorship? What’s in it for them to give up something so precious? How does that choice fundamentally shape an artistic practice? Matt DesLauriers illustrated this to me:

“With my approach to art, a lot of what I'm interested in is setting up a system and then letting the system run in some ways on its own—without my control over every aspect of it. There's something to this that I find much more captivating than a single image or artwork.”

Artists engaging with systems gain optionality. They have the option—as with Vera Molnár’s short-form generative art—to use their human intuition to select individual outputs. They also have the option to add a plurality and dynamism to otherwise singular, static work, as with DesLauriers. Why artists make this choice can often be one of the quickest ways to understand a practice.

Community

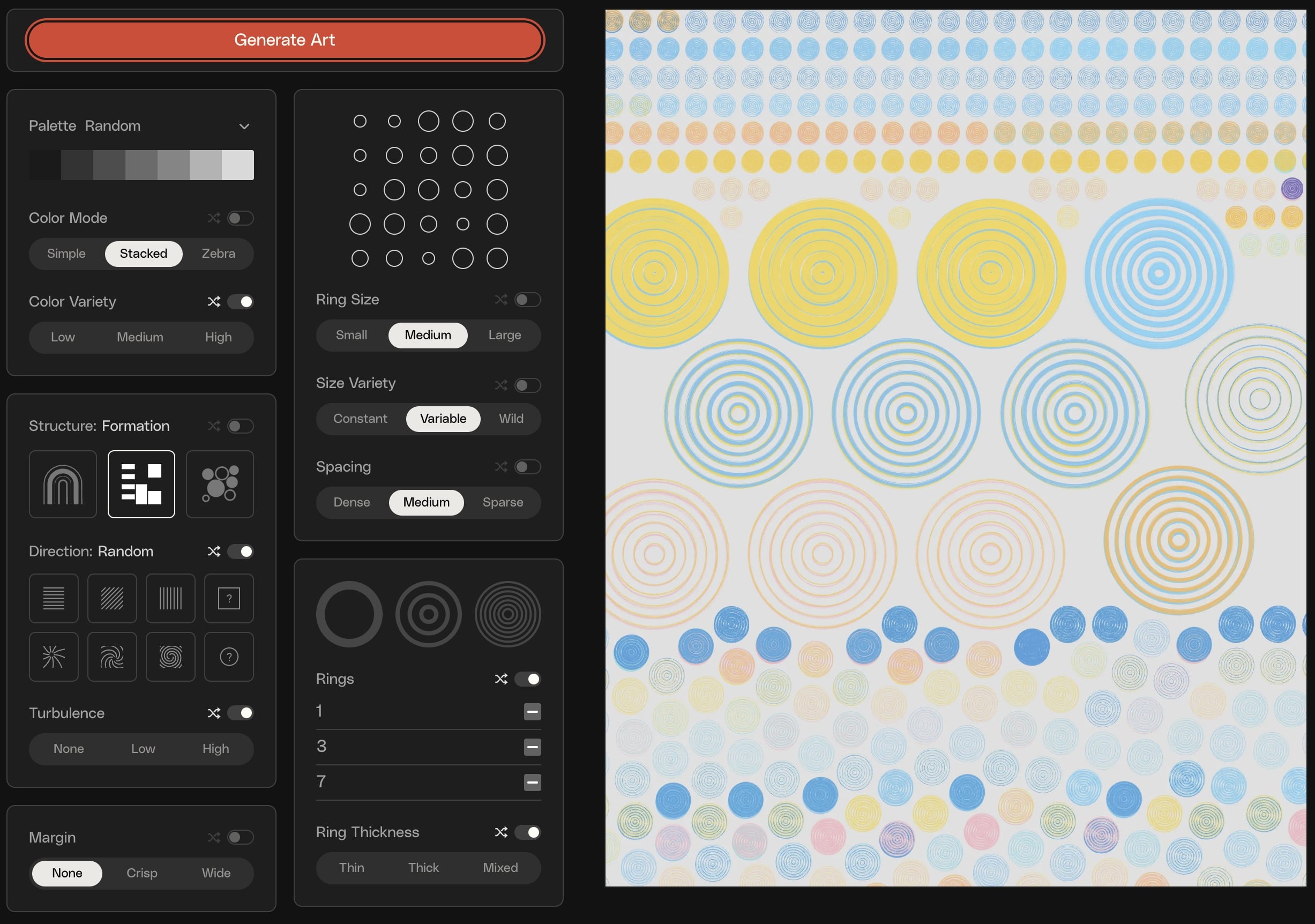

Artists can also cede control to systems that allow for further layers of creative input—increasing the distance between artist and results. This includes generative AI, parametric, interactive and participative work. This is like an artist creating a virtual world—sometimes literally—where you’re in an artist-controlled space but still have varying degrees of maneuverability. What are the creative implications of this artistic choice?

First, the artist’s level of authorship is reduced. Intuitively, this makes sense; artists have less authorship of a Midjourney piece created with commercial software than a GAN they trained themselves. How should authorship then be distributed amongst artist, system and participant?

Also, why again would an artist choose to share such levels of control? While it may sound limiting, it can paradoxically expand creative possibilities. Parametric systems, for instance, can be infinite—a way for the artist to create a world in their vision and share it with an audience to further explore. DesLauriers, again, explained to me:

“When you give the system not just to one other person but to thousands of people, you have the potential to create a lot of interesting, distinct variations on something where if it's just me doing it on my own, I'm more limited. That's one thing I really like about the openness of the parametric space.”

In an attention-driven world, creating art that engages communities will be increasingly relevant.

Collaborator

While procedural and communal systems exercise agency within an artist-created world, collaboration means building this world together. This requires the greatest levels of autonomy—perhaps even a shared artistic vision.

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s practice stands out for its radical openness and “Interdependence,” as well as the pertinent questions it poses about authorship. Not only do they collaborate with each other, they are also in deep conversations with their AI models, such as Holly+, other artists and their audience. Herndon and Dryhurst’s Holly+ undoubtedly has a critical community aspect but the artists position it as something bigger. Dryhurst explained to me how they see Holly+ as a public good that benefits others while reimagining their practice:

“We took this [public good] approach with Holly’s persona in Holly+, that in a sense the greatest honor one could achieve as an artist is to become infinite through adaptations made by others.” Does that make the persona Holly+ an artist? What degree of authorship does this AI “persona” have? The pair’s practice demonstrates the layers and complexity of authorship and autonomy: it can be distributed within a human pair, group, system or to potentially unlimited participants.

More clear-cut examples of systems-as-collaborator include Harold Cohen and AARON, Sougwen Chung and D.O.U.G. and Pindar Van Arman’s CloudPainter. Sougwen Chung explained it to me, saying, “I extend the work beyond architecting the system to propel a sensibility. I take the work further to implicate myself and the system within the space of a canvas.” For Chung, D.O.U.G. and “the systems we build are actually us in another form.” She continues, explaining how “the arm in D.O.U.G.1-5 is a symbol for an anthropomorphized human subject, the mechanical double.”

The clue to whether a system has reached collaborator level is if it’s given a human name, such as Holly+, AARON, and D.O.U.G.

.jpg)

What about a fully autonomous AI artist? For this, the AI would need to demonstrate agency beyond its programming. In other words, it would need to be fully independent and choose to make art—like in Lawrence Lek’s Geomancer—given viable alternatives or directives. We discuss agency, degrees of authorship, next.

Agency: How Much Autonomy?

If artists have control, then systems have agency—their own level of autonomy or independence. In the previous section, we discussed who or what artists can cede control to and whether systems can be considered authors. This section on agency allows us to taxonomize certain techniques and populate the chart above.

Procedural: Low Agency

Short-form generative art—among the lowest agency generative systems—allows artists to delegate control to algorithms for the precise formal specifics while retaining the ability to curate images from hundreds or thousands of outputs to define the “final work.” This represents a human-system-human process, where the algorithm generates ideas but the artist retains ultimate control.

Moving up in agency, long-form generative art platforms like Art Blocks, fx(hash) and Highlight introduce a human-system process where a user’s timing and transaction hash determine certain variables. The artist steps back, relinquishing their role as curator, with the system assuming greater agency over the final output. Whether artists curate outputs or grant that agency to a system, it carries profound creative implications for the algorithm’s construction.

Higher on the agency scale are custom-trained AI models, such as GANs. These models enable artists to train algorithms using thousands of carefully selected images, shaping the aesthetic and conceptual parameters of the generated outputs. While this training grants artists significant influence over the system's creative potential, GANs still operate within a bounded conceptual space defined by the artist's inputs. This differs markedly from the vast and unpredictable generative capacities of black-box models trained on millions or even billions of images, generative AI, which we discuss next.

Communal: Medium Agency

At the lowest level of communal agency is generative AI, where the “community” can be thought of as the collective media on which the model is trained. Generative AI tools, such as Midjourney or DALL-E, allow artists to precisely define prompts, but the lack of determinism and the opaque inner workings of deep learning neural networks necessitate that artists cede a significant level of control. Artist prompts guide the output but so too does the latent space formed from the vast datasets that power these models. While the artist guides the process, the agency of the system—and indirectly, the community whose data informs it—plays a critical role.

Increasing in agency are parametric projects like Tyler Hobbs’s QQL, which provide a more intentional framework for community participation. Here, the artist crafts a parametric space—a structured yet open creative sandbox—inviting the viewer to explore and shape outcomes by selecting specific parameters, like color palettes or shapes and sizes. This approach shifts more creative agency to the participant, allowing them to play an active role in determining the “final work.” However, this exploration is still guided by constraints and boundaries predefined by the artist, maintaining their overarching vision.

At the higher end of communal agency is interactive and participatory art, where audiences engage with the work in dynamic, often real-time ways, such as through keystrokes, motion capture or algorithmic interaction. Projects like Mathcastles by Terraforms, which rely on collective input to evolve their narratives and aesthetics, take communal autonomy even further. These systems not only form their own communities but they also empower them to transcend passive observation, granting them significant autonomy to shape the artwork’s trajectory within the artist-designed system.

Collaborative: High Agency

As we enter the more speculative end of the scale, perhaps the only level of collaborative agency achieved is the lowest level, human-machine collaboration, involving systems that act as extensions or tools of the artist. Here, the artist and the system co-create in a dialogic process, where the machine assists in achieving an artist’s vision but does not independently steer the creative direction. Sougwen Chung exemplifies this with her work alongside D.O.U.G. (Drawing Operations Unit: Generation X).

At a more advanced level of collaboration is the concept of co-inhabitance, where the boundaries between artist and system dissolve to the point of mutual creation. In this model, the machine is not merely an extension of the artist but a partner with its own agency within a carefully designed creative framework. Chung’s description of D.O.U.G. as a “mechanical double” reflects this philosophy, as does her vision for future systems where “materiality is foregrounded, and co-inhabitance is the aim, in which the human hand is always present.”

At the most extreme end of the agency scale lies fully autonomous AI, where the machine not only co-creates but acts independently, making creative decisions without human intervention. Here, the artist no longer has any control. While this degree of agency is still highly speculative, projects like BOTTO, where an AI generates art voted on by a decentralized community, give us a glimpse of what’s possible. Visions of what a fully autonomous AI might look like include many of the characters in the films of Lawrence Lek, where super-intelligent AI protagonists grapple with the implications of being confined to their systems.

.jpg)

Where an art practice exists along this scale reflects any number of creative choices. These include: What are the artists’ constraints?” Why/how were these chosen? And how much does the artist wish to reveal of their own self? These are questions of creativity.

Creativity: What’s Done with Autonomy?

Artists have shared control and we understand better now to what extent they maintain or share control. What does this investigation reveal about the creative process? Two examples of how autonomy impacts creativity are the related concepts of “handedness” and constraints. We then look at the types of systems creativity.

Handedness refers to the amount of individual style visible in outputs—how much authorship is identifiable in the “final work”? It can also be thought of as the human element of generative art, as Zach Lieberman explained to me. Some artists prefer their style or hand to remain, like Sougwen Chung—to personalize their work—while others intentionally look to avoid revealing their personal signature, such as Paul Brown. By examining handedness in generative work, we add depth to our understanding, performing archaeological excavations to identify clues. Or as Chung explained to me, “In each work of generative art nests a question—what is the role of the human hand?”

Constraints are a related concept that further connects the human with questions of autonomy. Artist Karsten Schmidt (Toxi) thinks of the constraints that artists impose on their system as “biases” and “subjectivity.” Examining constraints, why the artists chose them and what they reveal about a practice remains one of the most worthy lines of questioning.

Besides handedness and constraints, we can think about the different types of creativity that a system might display. We use Margaret Boden’s categorizations of creativity, which also relate to the procedural, communal and collaborative categories of autonomy. Boden breaks down creativity—which she defines as “ideas that are new, surprising, and valuable”—into three types: combinational, exploratory and transformational.

Combinational Creativity—Procedural Systems

According to Boden, “combinational creativity involves the generation of unfamiliar (and interesting) combinations of familiar ideas.” Boden explains that “many attempts to define creativity, even within the specialist psychological literature, confine it to this first type alone.” Combinational creativity corresponds to the creativity exhibited by procedural systems, typically in the form of computers and code that are particularly capable of generating surprising combinations of ideas, especially rapidly at scale. Machines have utilized combinational creativity since at least Ramón Llull’s “logic machine” nearly eight hundred years ago, continuing through to the invention of computers.

Primitive forms of AI have been capable of achieving this level of creativity since at least David Cope’s EMI from the early 1980s, which, according to Cope, “uses its output to compose new examples of music in the style of the music in its database without replicating any of those pieces exactly.” This combinatorial system could best be thought of as sophisticated mimicry.

Exploratory Creativity—Communal Systems

But exploratory creativity is different, exploring the possibilities within a given conceptual space—like when artists create parametric spaces or AI’s latent space. For example, Cope’s EMI could combine elements to produce plausible Bach compositions but it couldn’t create a work in the style of Debussy with Senegalese drumming and electronic synths. Generative AI allows for traversing a latent space conceptually richer than Cope’s imitation.

Exploratory creativity involves generating new ideas by navigating and experimenting within established frameworks. This applies to autonomy, where the artist creates a space for the audience’s combined creativity to exceed what they could have achieved on their own.

Another way to think about creative exploration in a communal system is as tweaking. Christiane Paul explained to me how tweaking differs from collaborative creativity: “Harold Cohen, of course, really conceived AARON as a collaborator, as another self. He encoded his vision of art into this system. That is very different from artists working with tools, even if they're doing it in very sophisticated ways—such as Stable Diffusion, DALL-E or Midjourney—because they are more engaged with a dialog of tweaking an existing optimized system.”

Transformational Creativity—Collaborative Systems

If exploring involves tweaking a model, transformational creativity is transcending. AI has already exhibited the previous two types of creativity, but it’s less clear whether it has achieved this most radical form of creativity, which rethinks the rules of a conceptual space itself. According to Boden, “The resulting change is so marked that the new idea may be difficult to accept, or even to understand.” In art history, these would include moments like Picasso and Braque's Cubism, Duchamp’s Conceptualism, Frieder Nake’s Computer Art, David Cope’s EMI, JODI’s net.art and Rhea Myers’s blockchain art.

Transformational creativity aligns with the creativity of collaborative systems, where we can no longer so easily distinguish between system and artist. Collaborative systems permit the artist to transcend their own individuality. Collaborators Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze put it like this in A Thousand Plateaus:

“To reach, not the point where one no longer says I, but the point where it is no longer of any importance whether one says I. We are no longer ourselves.” Deleuze and Guattari echo Cohen and Chung’s dissolved sense of self.

Humans can achieve transformational creativity with or without machines. Can AI achieve transformational creativity? Any capable AI system would need to be nearly fully autonomous. Transformational creativity requires a deep understanding of the underlying dimensions of a conceptual space as well as the agency and ability to radically redefine or abandon these dimensions. These qualities demand intentionality and contextual awareness that AI currently seems to lack. True autonomous transformational creativity may only be achievable with Lekian fully autonomous AI.

.jpg)

While Boden speaks of combinational, exploratory and transformational creativity in broad terms, I mean them specifically as they relate to a system’s capacity to be “creative.” Human creativity cannot be so easily categorized and can vary from one project—even idea—to another. It’s still up to humans to utilize their own creativity in combination with the system creativity described above.

Closing

Why generativity? Why autonomy, authorship, agency and creativity (AAAC)? What do they reveal about making art today?

Not only can considering AAAC help us—or be necessary—to understand an artistic practice or generative art itself by revealing the intricacies of the relationships between artist, system and audience. These concepts can also highlight our own relationship with technology and its impact on our daily lives. How much control do I maintain—or cede—to the technologies and systems that increasingly encroach upon my self? How much agency does technology have over me and my well-being? To what extent do I author my own life?

Generative art compels us to confront the agency of systems and their impact on creativity and authorship. At the same time, it reflects broader societal questions: How much do we shape the technologies we use and how much do they shape us?

Read Part I: Demystifying Generative Art

Read Part II: Demystifying Generative Aesthetics

Read Part III: Demystifying Generative Systems

---

1 Margaret A. Boden. "Creativity: How Does It Work?" 2007.

---

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.

Special thanks to Margaret Boden and Ernest Edmonds, whose writing and thoughts contributed to this work.