Post(human)-AI Art

Post(human)-AI Art

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) explores the concept of "Post-AI Art," positioning it as a significant departure from "AI Art." Bauman posits that Post-AI Art rejects human-centric views, embracing a posthumanist perspective that emphasizes interdependence, entanglement and co-inhabitation between humans and non-humans, including AI.

Did you hear? The human is dead. Actually, it's a cold case. But there are leads.

Nietzsche killed (god and) humans well over a century ago in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883), when he described the fixed, rational human as a bridge to the Übermensch: “man is something that must be surpassed.”

For Foucault in The Order of Things (1966), “man is a recent invention…and one perhaps nearing its end.” He argued that the human as we know it, speaking, laboring, knowing, being, emerged only in the eighteenth century as a byproduct of disciplinary regimes and epistemic structures. Just as it emerged, it could dissolve.

Derrida spoke in “The Animal That Therefore I Am” (2002) about deconstructing strict lines between human and animal, resisting human nature to “other” non-humans and exposing our anthropocentric tendency to caricaturize animals.

Donna Haraway expanded this posthumanist tradition to include machines in "A Cyborg Manifesto” (1985), collapsing fixed notions of organism and machine, embracing the cyborg as a feminist, empowered figure.

Most recently, James Bridle asked us to rethink intelligence, decenter the human and question modern rationality in the context of deep learning breakthroughs in Ways of Being (2022).

This through line of posthumanist thought must not be confused with transhumanism, which centers technological solutionism to upgrade humans and is favored by tech oligarchs. Think less enhancements (transhumanism) and more relationships (posthumanism).

Stop, Stop, It’s Already Dead!

Okay, the human is dead. What does that mean? Human extinction? No(t necessarily). Are human-centered practices or concerns dead? Of course not. Artists should make the art they want, always.

Seeing Post-AI Art as a reassertion of human privilege in creativity, however, as artist David Young suggests, offers little in the way of artistic advancement. Nor does it reflect the most incisive and ambitious interventions with AI over the last few years. The view also sidesteps a direct engagement with the legacies of AI Art’s first decade.

After all, deep learning AI Art’s first decade was already dominated by the human, especially formally with the human face. Its replication was one of deep generative modeling’s earliest—obsessions, er—tasks. For over five years—from 2014 with Ian Goodfellow’s original GAN paper to Phillip Wang’s 2019 work “ThisPersonDoesNotExist”—the most human signature of all, the face, was elevated.

.jpg)

This emphasis prompted Entangled Others (Sofia Crespo and Feileacan McCormick) to do something Post-AI back in 2020, to look away from the face, as “very much a response to those early moments being so human-centric!” according to McCormick.

Does rejecting this human-centric viewpoint mean claiming that the needs of a tree equal the needs of a refugee? Of course not.

Becoming less selfish doesn’t require a strict, self-flagellant denial. It means greater empathy, tolerance and the humility to accept that we’re part of a larger whole.

It also means the altruism to act for the benefit of others from time to time—even at an occasional cost to yourself.

Post-AI’s interests extend past last decade’s first-order questions like “Can machines be creative?” or “Can machines make art?” Instead, it asks second-order questions, like, “What new forms of ecological subjectivity emerge when humans are no longer the sole intelligent creators?”

But how radical of an idea is Post-AI?

Post-AI’s Baggage

Post-AI Art is not a new term. It was coined at least in 2018 by Addie Wagenknecht. Theorists like Joanna Zylinska and Martin Zeilinger have already even described the Post-AI condition as “entangled” and connected it to posthumanism. There are also divergent readings, offered by Young, Anika Meier, and Kevin Esherick, of what Post-AI might ultimately signify.

Then, while not explicitly calling itself “Post-AI,” another compelling theory is Mat Dryhurst’s Protocol Art, which strikes a more ambitious tone. Dryhurst explained to me, “Protocol art is basically suggesting that most consequential activity for culture and society happens upstream of media. The training of the model is responsible for the media that comes out of it.” For Dryhurst, however, Protocol Art encompasses all media. Post-AI Art, by contrast, speaks specifically to AI media and to the material and conceptual reverberations that deep learning technologies exert on creativity.

Rather than coin, this piece aims to sharpen and consolidate Post-AI’s meaning so it can become a more meaningful and useful term, particularly in contrast to simply “AI Art.”

It also aims to draw connections from the emergence of AI to net art and Post-Internet Art. This juxtaposition aligns AI Art and Post-AI Art with those canonized art historical traditions while also providing a point of departure from which to better understand where we are today and where we may be headed.

“Post” may also need some clarification because it does not mean a crude break or total rejection. It’s an absorption and reorients the initial concerns of AI Art, signalling a new condition for artists to address.

It’s also not temporal. We are not beyond AI, just like Post-Internet and post-digital never signified we had moved beyond the internet. The internet didn’t go anywhere. It became the air we breathe, invisible but constantly present and affecting us, our bodies unconsciously responding to it.

Post-AI also doesn’t mean an end to critically engaging with AI and art; quite the opposite. A “post” conception of AI resonates with ecological thinking, inherently asking how we can be better stewards of the various artificial and natural ecologies we disrupt.

But before we get into Post-AI Art’s core tenets, it’s worth investigating its striking parallels with art’s response to the rise of the Internet.

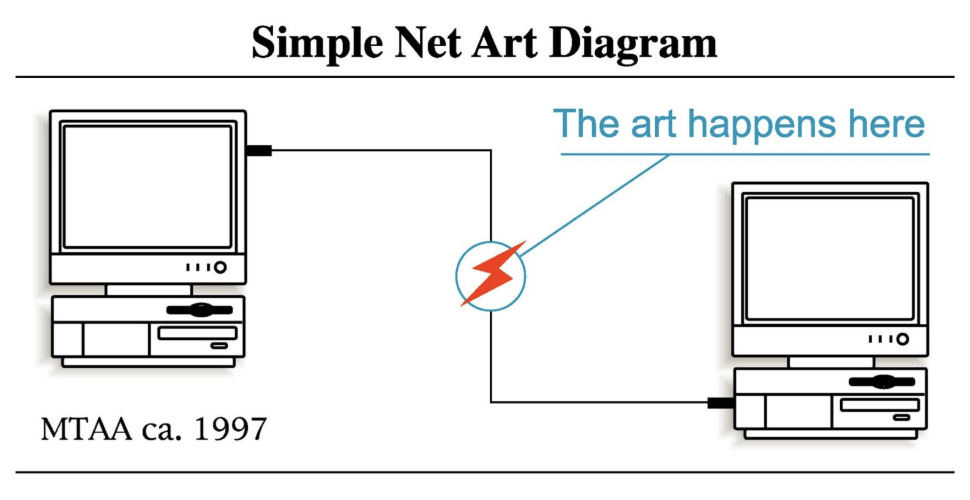

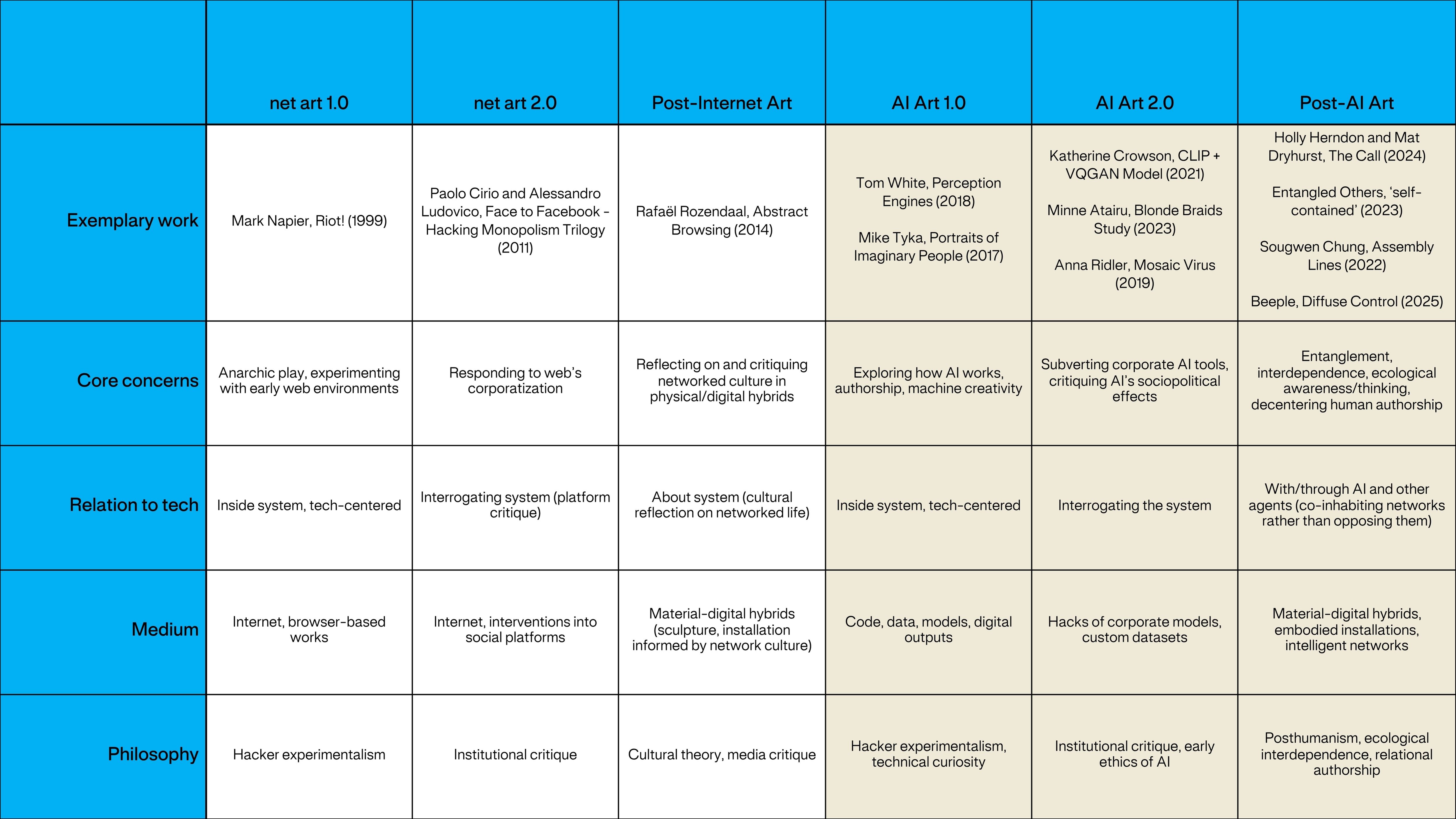

net art → AI Art, as Post-Internet → Post-AI

Deep learning AI Art of the 2010s by Gene Kogan, Anna Ridler, Memo Akten and others parallels the 1990s net art of Olia Lialina, Vuk Cosic and Mark Napier. Both emerged from artists’ first encounters with transformative technologies. Both were driven by curiosity about how the technology functioned, what possibilities it unlocked and how it could be subverted. In each case, artists worked inside the system itself: net artists with web browsers and AI artists with datasets and models.

Net art 1.0 and 2.0

Whitney’s curator of digital art, Christiane Paul, has identified two periods of net art. Net art 1.0 began in 1994, marked by an “anarchic playfulness.” An example is Mark Napier’s Riot! (1999), which subversively blended early web pages together in homage to the Tompkins Square Riots and what Napier saw as state-sponsored gentrification. In its second decade with 2.0, net art experienced something “more aggressive,” focusing on interventions with the Internet’s forming megacorps, Google, Facebook and Amazon. Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico’s Face to Facebook (2011) demonstrated this by republishing scraped Facebook profiles on a fake dating site to expose social media’s extractive use of surveillance and privacy terms.

AI Art 1.0 and 2.0

AI Art followed a comparable arc. Its first decade was defined by experimentation and a playful probing of the medium’s possibilities, as seen in the work of Tom White’s Perception Engines (2018) or Sarah Meyohas’s Cloud of Petals (2016). Like net artists, they operated within the system to reveal deep learning AI’s capacities, quirks and constraints.

In the second decade (2020s) with 2.0, this all changed as corporations with LLMs and generative AI models entered the picture. AI was no longer the exclusive domain of those technical enough to navigate it or harness enough compute. Anyone could now use ChatGPT and DALL-E 2, which demonstrated AI’s capabilities like online shopping, search, streaming and socializing did with the Internet in the 2000s. Interventions with AI became more about subverting these corporate tools, like Katherine Crowson and Ryan Murdock’s hacking of CLIP with various GANs to create free and open early text-to-image models or Minne Atairu’s Blonde Braids Study.

Post-Internet Art and Post-AI Art

Post-Internet Art emerged twenty years after the internet’s arrival, once it had become properly ubiquitous. The term signified a shifting focus from making art within the web (net art) to a more material, digital-physical hybrid making that reflected and critiqued the aesthetics and culture of a fully networked world. It was a direct response to net art’s immaterial digital condition and subsequent corporatization. Exemplary Post-Internet Art includes the work of Petra Cortright, Cory Arcangel and Rafaël Rozendaal, who oscillate between digital and physical iterations.

Post-AI art parallels this trajectory, emerging as AI shifts from experimental to infrastructural, increasingly dominated by corporate models. But it, of course, asks its own new questions and hints at new futures.

Post-AI Art’s Core Tenets

Post AI Art absorbs the first decade of AI Art’s first-order concerns—autonomy, authorship, machine creativity—and reframes them through a second-order, interdependent and posthumanist lens. With the human no longer the singular creative agent, creativity becomes a negotiation among multiple entangled intelligences.

Entanglement: Reimagining authorship and fostering collective practices

At Post-AI Art’s core are concepts of entanglement, interdependence and co-inhabitance, exemplified by the practices of Entangled Others, Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst and Sougwen Chung, respectively. In these practices, AI functions as more than collaborator, becoming an indistinguishable component of the process, like adding eggs to batter.

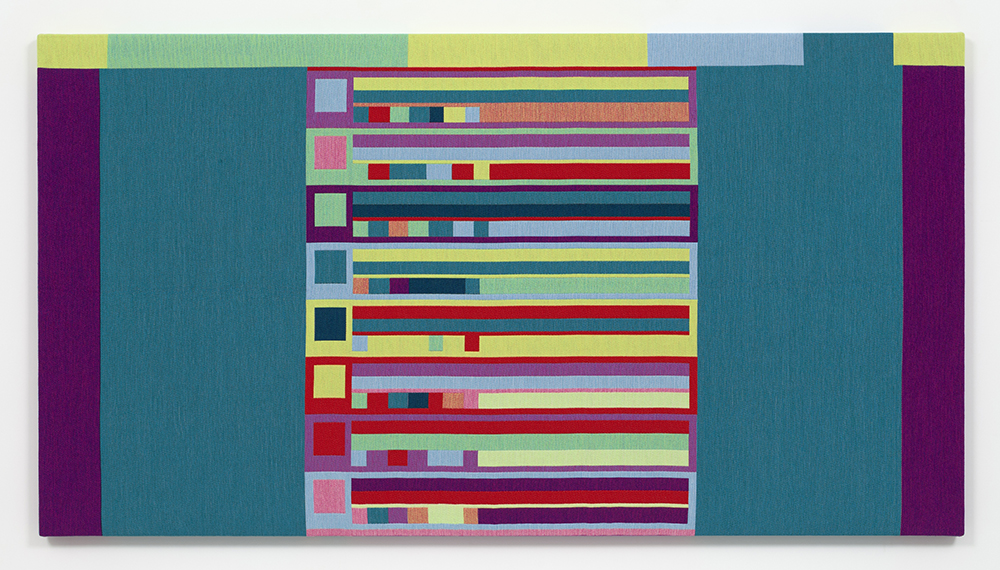

The very name, "Entangled Others," reflects this idea of the imaginary separation between things. For the duo, entanglement applies to their own relationship as well as the "interconnectedness of all living beings." In works like ‘self-contained’ they weave data, natural systems and biological material into a single continuum, where distinctions between human, machine and environment fall away.

Herndon and Dryhurst’s The Call reframes authorship as a living protocol, distributing voice and agency across human choirs and AI surrogates. It casts creation as a collective but fair process where consent is essential.

In Sougwen Chung’s Assembly Lines, the Drawing Operations Unit Gen 5 (D.O.U.G._5) translates meditation and biofeedback into painterly gestures that entwine with Chung’s hand, producing a choreography where human and machine authorship become indistinguishable.

Together, these works recognize that art is always already made with others, human and nonhuman alike, within a living creative ecology.

Decentering human creativity

As previously mentioned, the posthumanist tradition, including Nietzsche, Haraway and Bridle, grounds Post-AI in a tradition where the human and our concerns are no longer the unquestioned point of origin or ultimate measure of creativity. Instead, Post-AI situates artistic production within a constellation of relations where human needs no longer dominate.

Emphasis on embodiment and materiality

As Post-Internet and Post-Digital responded to net art’s disembodied virtuality, Post-AI counters AI Art’s emphasis on technical immateriality with embodied and physical experiences. Beeple’s Diffuse Control, Herndon and Dryhurst’s The Call, and Entangled Others’s ‘self-contained’—whose images are encoded as DNA and sealed within a sculptural capsule—embed AI within lived, sensory environments where human and nonhuman agencies converge. These projects recast AI in physical space, something to be negotiated with and moved alongside. As Entangled Others assert, “There is no actual line you can draw between what is digital and what is physical.”

Challenging the notion of speed, imitation and Pre-Modernity

A Post-AI orientation slows things down. Against the corporate acceleration of AI models and the fetish for novelty and speed, Post-AI Art values duration and idiosyncrasy. It resists the flattening of creativity into mere imitation or style transfer, again, responding to the first decade of AI Art’s emphasis on unlimited production at scale. Sougwen Chung told me how their practice involves "different modes of temporality" and takes a "very long time" to create systems, emphasizing a desire for slowness over "infinite image generation."

Ecological awareness and impact

Finally, Post-AI Art is ecological. It is attuned to the networks—biological, computational, cultural, political, societal—within which art is made and through which it circulates. Without seeking to dominate or escape these systems, Post-AI artists inhabit them responsibly and ethically, acknowledging their fragility and our shared stake in them. This means AI’s ethical concerns are not forgotten with Post-AI but reinvigorated, with awareness of their effects baked into its practices.

Closing (almost)

What this analysis may point to is a pattern (experimentation ⇒ interrogation ⇒ integration) for how artists have historically responded to wildly disruptive emerging technologies. A similar motif occurred with the rise of the digital in the ‘60s through the ‘80s. That timeframe perhaps highlights another key but intuitive insight: the time period is shortening between a form’s experimental emergence and its “post” adoption ubiquity. It took the digital at least three decades. It took the internet two decades. And it seemed to only take deep learning one.

That means less time to adjust to compoundingly complex upheavals.

It’s no coincidence that artists foregrounding posthumanism and interdependence were drawn to AI, the natural medium for these increasingly relevant concerns. The medium follows their artistic inquiry, marking a key distinction from AI Art, where the medium itself was frequently the focus.

Thus, Post-AI Art signals a shift in how we think, make and relate in the age of AI. It’s a reminder that we must now live not only with the technology but within it: critically, creatively and humbly.

A Post-AI perspective revels in a new world that’s stranger, more complex and inscrutable than we could have imagined even a decade ago. But it’s also more exciting. Nervousness and excitement often feel the same; they’re natural responses that something important is happening. Post-AI captures the entanglement of nervousness and excitement we all naturally feel towards this recentering world.

So What’s Next? Post ___?

This all might beg the question, “If we are already living in a Post-AI world, what’s next?” Artists will decide, with their work. But several prominent practitioners already seem to have a fairly clear idea, independently arriving at similar conclusions. I tend to agree.

Coming soon! What’s after Post-AI? Post…

----

Peter Bauman (Monk Antony) is Le Random's editor in chief.